Code Neutral

Series: practices October 26, 2015

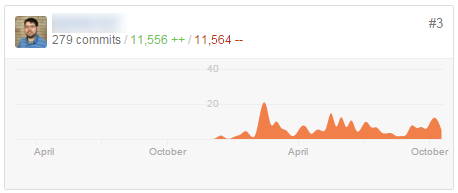

I’m rolling off a long-running project after a year and I recently became “code neutral” (ala carbon neutral) for the main code repository. Over 279 commits, I added 11556 lines of code and removed 11564 lines of code (net of -8 lines).

At first, the idea of code neutrality was just an amusing anecdote that I heard about on The Bike Shed podcast. But the more I thought about it, the more I could see the value.

I mentioned my “quest” to delete code to a co-worker and we talked about some of the benefits:

- Less complexity (no extra code for dead features)

- Less confusion (“I don’t understand why this code even exists”)

- Faster build/compile times (ok, maybe not a huge difference…)

- Small surface area for bugs and errors (we had at least one production error due to code that we didn’t even need)

- Feels good to add features while removing code

Cleaning up a bunch of unused code is like cleaning your desk. If you don’t do it periodically, it just breeds a larger mess. We don’t want people to start thinking it’s okay to leave big chunks of unused code in the project.

(Note: I am not interested in “cheating” by removing whitespace or re-formatting code to artificially inflate my stats. Only legitimate removals were allowed!)

Over a couple of weeks, I would actively try to remove code from the project. I noticed a few themes and identified some hot-spots that seem generally applicable.

Code that is simply unused

The project is mostly Java so my IDE was kind enough to do the heavy lifting of finding unused code. I found some local variables that weren’t used. There were some methods and fields that were either unused or used only in tests of their own existence. We have an automated check to fail the build on unused imports, but that is another easy win.

You might ask why not automate this kind of deletion? I would love to. But while the project is mostly agreeable to static analysis, there are some gotchas.

Fields that appear unused to IntelliJ might be used via reflection (because Spring…) or be referenced in a view template or in JavaScript. Anything that looked legitimate needed a more thorough investigation (or supreme confidence in the thoroughness of the test suite).

The loose coupling of views, controllers, and front-end assets presents a challenge for static analysis, but it was a goldmine for finding code to remove.

I found instances where a controller endpoint was removed, but we forgot to delete the view template. I found instances where a view template was removed, but we forgot to delete the CSS file. And even in the cases when we got all of those, we sometimes forgot those pesky translation values.

Planning for a future that never arrives

My favorite code to remove was code that we thought we might need, but never did. While practicing TDD can help you write only the minimum amount of code you need, sometimes things fall through the cracks. We’ve all been there; we write some code to get the color of a widget and we just know we’ll be needing the shape eventually, so let’s just add it now.

Except a surprising amount of times, you don’t end up needing it. If it is “quick and easy” to add it now (just in case!) then it should be quick and easy to add it later when you are sure it belongs.

I encountered a number of code paths that lead me through a winding maze of classes and methods, only to end with a tragic “NotImplementedException”. In a multi-layered web architecture (e.g. controller -> service -> repository), you can end up implementing quite a bit of “stubbed out” code that leads to a dead-end. It felt really good to delete this code.

Anecdotally, the “future-proofed” code I found was often added as part of huge, multi-file commits. I’ll speculate that smaller commits might have kept the changes more focused and made it easier to identify unneeded code in reviews.

Leftover framework/tooling cruft

I spent one session looking through all the config files for our tools, looking for customizations that no longer mattered or references to files that no longer exist. One notable example was a security configuration that white-listed a bunch of URLs. Several of the URLs had been renamed or removed and the config file had fallen out of sync.

I was making good progress, but I started running out of lines to remove. Then, I found the motherload.

In any long-running project, new tooling gets added and (hopefully) some of the old tooling goes away over time. In our case, an end-to-end testing tool had been added in the summer of 2014. Ultimately, a different tool was adopted later that year and all remains of the old tool were deleted. Or so we thought…

We accidentally left behind a whole package (10+ classes) of boilerplate helper code for a test suite that was long forgotten. This discovery finally bumped me over the edge and I hit code neutral!

I’m not sure how reasonable it is for everyone to remove more lines than they’ve added, especially on a project that is still under active development. While we can strive to build features with the minimal amount of code, creating new functionality is usually a net-addition of code. But it was fun to try to get closer to neutral, even if getting all the way to zero isn’t always feasible.

It might seem silly to care so much about this number. But I think it was actually a productive use of my time as I wound down on the project. In the end, it was really satisfying to have removed more than I added to the codebase (while adding a year’s worth of new functionality). The codebase will be a little nicer and a little smaller for those that will continue working on it.